In the time before their kingdom’s conversion to Christianity, the Armenians were pagans, worshipping deities of fire, water, and the sun. Indeed, the exact roots of the original Armenian religion are a bit difficult to identify. At its base, there appears to have been an inherited Mesopotamian root – the worship of Khaldi, Teisheba, and Shivini being documented in the Urartian kingdom. There is also evidence that early Armenians revered the phenomena of nature, in particular the sun.

Chief among their deities was Ara, the physical embodiment of the sun, and the Armenians called themselves the Children of the Sun. Over time, Armenian religion would be heavily influenced by the experience of the Iranians and later – the Greeks. Indeed, during the era of Persian dominance, Mihr, related to the Persian Mithra, began be worshiped as the god of fire. Also noteworthy was the goddess of fertility, love, as well as water sources and springs – Anahit, who is still celebrated by Armenians to this present day.

On the day of Vardavar, usually celebrated in June or July, Armenians playfully drench each other in water, to celebrate the summer. Later, during the Hellenistic period, Armenian deities began to be depicted with human images, contrary to Iranian tradition. Indeed, through the interpretatio graeca, Anahit would, for example, be associated with Aphrodite.

Concerning Garni Temple

During my travels to Armenia, I found myself in Garni, a small town located to the east of Yerevan. Perched along the arid cliffs overlooking the meandering river Azat, the town is famous for the impressive Temple of Garni. In a land of endless churches, the ancient temple stands out no less impressively than the Parthenon in Athens or the Pantheon in Rome.

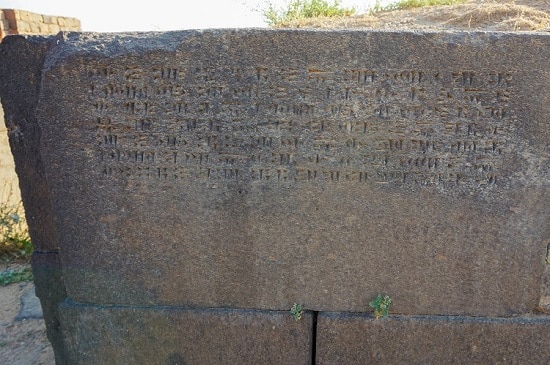

Tradition holds that the monument was first built during the 1st century of our era by the Armenian king Tiridates as a temple dedicated to Mihr. The evidence for this lies in an unearthed Greek inscription naming a certain Tiridates Helios as the founder of the temple. Indeed, during early nineteenth century, the Scottish traveler, Robert Ker Porter, recorded that the locals referred to the Temple as the Tackt-i-Tiridate (throne of Tiridates) in the Persian language.

The area is part of an impressive natural fortress complex, towering 300 feet over the river Azat below, and beyond it – lush, green forests teeming with deer, antelope, and leopards. The area feels almost like a sacred place, the Khosrov Forest providing a geographical respite from the increasingly dry and arid lands of southern Armenia. Beyond, the forest ends with the rising slopes of the Gegham mountains in the background.

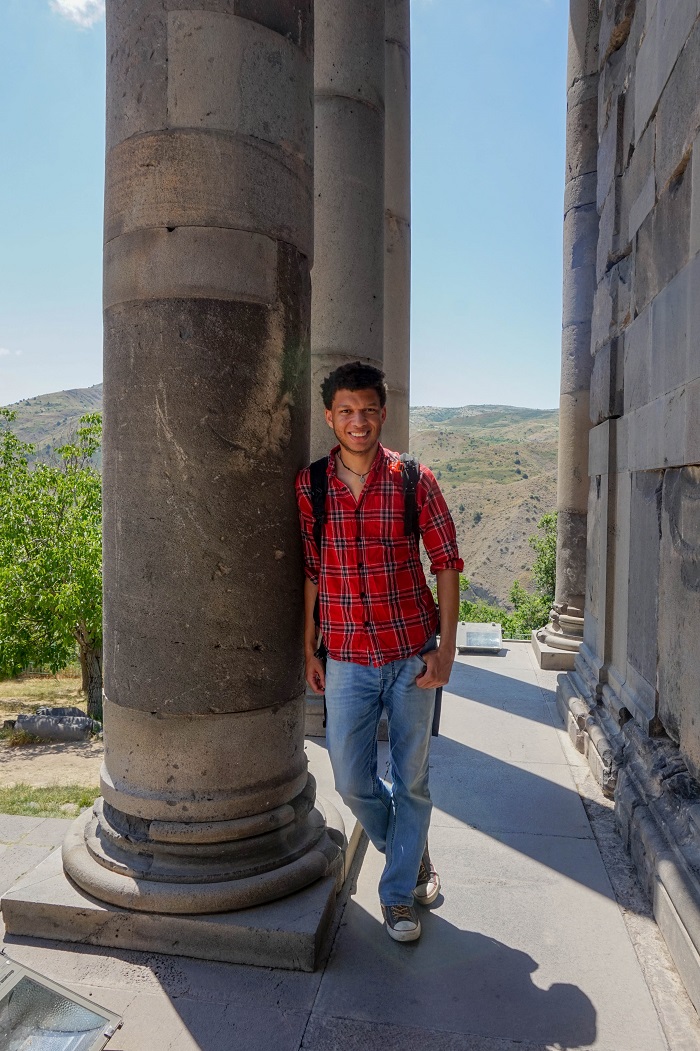

On the plateau, the fortress complex also houses the ruins of a Roman style bathhouse and the ruins of a Christian church. The colonnaded Temple of Garni was built in the Hellenistic style, indeed the only surviving example of such a temple in Armenia and the territory of the former Soviet Union. The temple is a peripteros, a temple surrounded by a portico with columns, built on an elevate podium.

From my own observations, I noted that the cella is surprisingly small, suggesting that worshippers stood outside the building, while a priest performed ceremonies and sacrifices in full view of the audience. It is possible that a statue of Mihr once stood inside the cella. There are surprisingly large steps outside of the temple of which I found more difficult than expected to climb.

Destruction and Survival

The obvious pagan nature of the temple begs the question – how did it manage to survive Armenia’s conversion to Christianity during the 4th century and the systematic razing of pagan monuments that succeeded it? The simple argument is that the temple may have been converted to a Christian church at some point. However, if this is truly the case then why was there a church built nearby during the 7th century? There is a theory that the temple was in fact – the tomb of a Roman client king, and therefore – a symbol of Rome’s authority in Armenia, one that would not have been undermined by their subsequent conversions to the Christian faith. There is also a legend that the temple’s survival can be traced to the efforts of Princess Khosrovdoukht, the sister of Tiridates III, who pleaded with her brother to spare the pagan temple.

Be that as it may, the temple survived until 1679 until it was hit by a devastating earthquake, centered squarely in the Garni gorge. The earth tempest reduced the structure to rubble and so it remained over the next three centuries. The massive ruins became the stuff of fascination for European travelers, and it would not be until the 1970s that the Soviet Armenian government would approve the reconstruction of the site under the auspices of the archaeologist Alexander Sahinian.

Remarkably, over 80% of the original stones were used during the reconstruction, with the additional stone being made clearly visible for historical purposes. Today, the temple is a popular stop among travelers to Armenia and is even the site for Vardavar and Trndez (another Armenian celebration of pagan origin, connected with sun/fire worship) celebrations. Standing proudly over the Azat valley, the Temple of Garni stands as a testament to Armenia’s classical history and hints towards its even older pagan past.

—

Interested in learning more about the grassy steppes, meandering rivers, historical sites, and diverse peoples that shape the eastern regions of the world? Indy Guide has the largest selection local guides, drivers, tour operators and hosts in underrated destinations such as Central Asia, Caucasus, Russia & Mongolia.