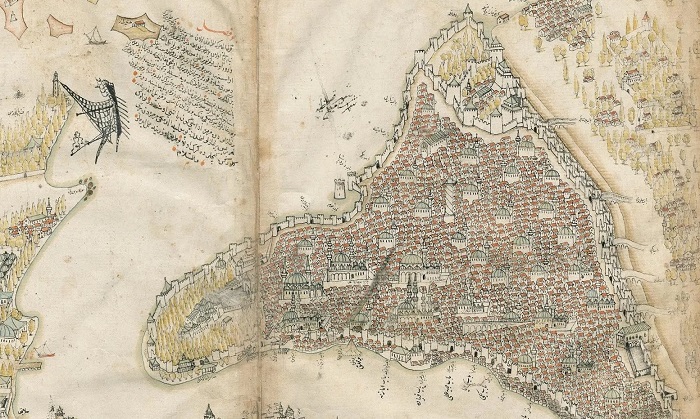

It is very easy to miss the sixth century Roman church of Hagia Eirene. It is a rather small structure, completely eclipsed by its larger and more famous sister church – Hagia Sophia, of which countless stories have been told. Beyond that, it is also located within the courtyard of the Topkapi Palace, and is known to the Turks as Aya İrini. The name, stemming from the Greek Αγία Ειρήνη means “Divine Peace.” All the same, Hagia Eirene is one of the most prominent landmarks of Constantinople, visible from throughout the city, and has its own unique stories to tell.

The Original Hagia Eirene

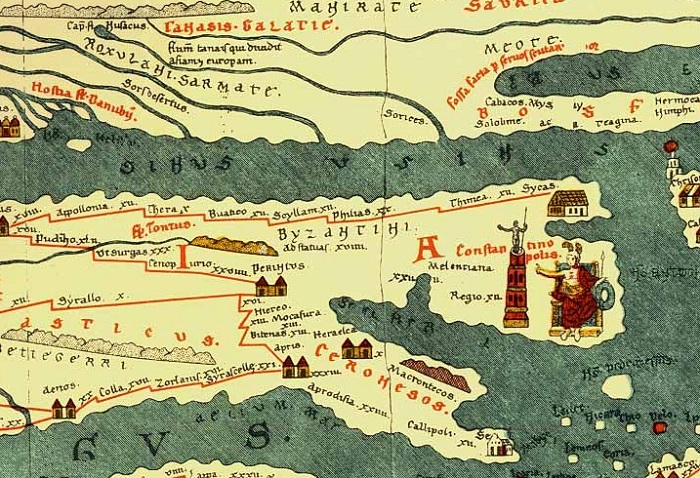

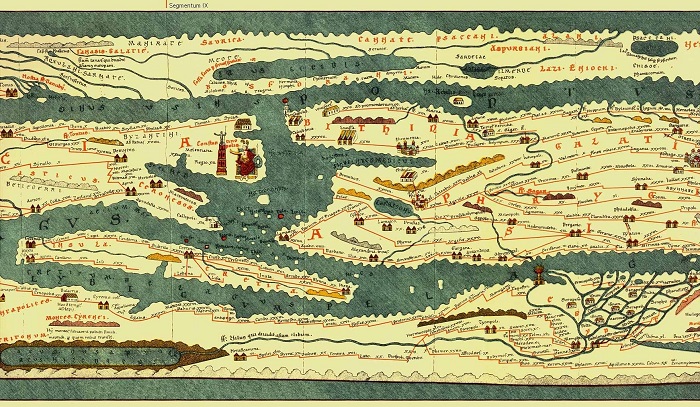

The current structure is not the original Hagia Eirene. During the time of the pagan emperors, the site was the location of a temple to Aphrodite. During the reign of Constantine the Great, a small wooden church was built there. It was known as the Αρχαία Εκκλησία, or the Old Church, and served as the capital’s main cathedral until the inauguration of the original Hagia Sophia in AD 360. It is even possible that the First Ecumenical Council of Constantinople was held in Hagia Eirene in AD 381. The church was a part of the same episcopal enclosure as Hagia Sophia and once held the relics of St. John Chrysostom, before being transferred to the Church of the Holy Apostles.

The original Hagia Sophia featured a wooden roof, which would prove to be its bane. During a series of riots against the Emperor Arkadios in AD 404, the structure burned to the ground. It is likely that as a result, Hagia Eirene again became the main cathedral of Constantinople, until Hagia Sophia would be rebuilt under his successor, Theodosios II. Unfortunately, Hagia Eirene would not survive the Nika Revolt a century later, and would also share Hagia Sophia’s fate in being destroyed again in AD 532.

Justinian’s Church

Hagia Eirene would be rebuilt by the Emperor Justinian in AD 548, employing the same architectural styles characteristic of early Byzantine architecture. The church would be damaged again by an earthquake during the eighth century and subsequently repaired. However, the structure of today’s church is based on Justinian’s construction.

Outside of the church, near its base can be seen some ruins. They are not from the original Hagia Eirene structure, but rather the ruins of the Hospital of Sampson. Legend says that the hospital was built in honor of Sampson, a physician from Rome who helped cure Emperor Justinian from the plague. According to Prokopios in De Aedificiis (On the Buildings), he wrote the following of the hospital:

“The church called after Eirene, which was next to the Great Church and had been burned down together with it, the Emperor Justinian rebuilt on a large scale, so that it was scarcely second to any of the churches in Byzantium, save that of Sophia. And between these two churches there was a certain hospice, devoted to those who were at once destitute and suffering from serious illness, those who were, namely, suffering in loss of both property and health. 15 This was erected in early times by a certain pious man, Samson by name. And neither did this remain untouched by the rioters, but it caught fire together with the churches on either side of it and was destroyed. The Emperor Justinian rebuilt it, making it a nobler building in the beauty of its structure, and much larger in the number of its rooms. He has also endowed it with a generous annual income of money, to the end that through all time the ills of more sufferers may be cured.“

The hospital was free to all, including the poor and would serve Constantinople over the next six centuries.

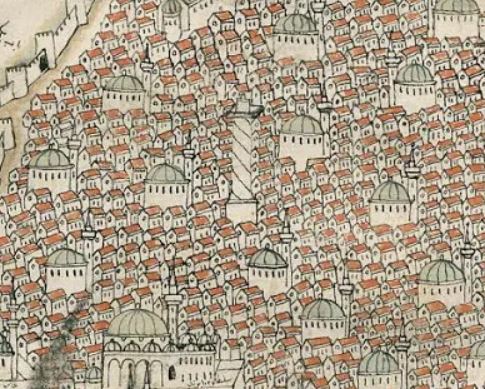

Upon entering, the first thing I noted that while Hagia Sophia is filled with tourists, warmth, and light, Hagia Eirene is empty, could, and rather uninviting. Except for a bored guard at the entrance, the only other occupants were a flock of birds who had decided to make the ruined church into its home.

During the times of the Romans, the church’s walls would have been covered in mosaics and frescoes, as can still be found in Hagia Sophia. However, they have all suffered from the ravages of time, and only fragments can be found throughout the structure today – particularly along the south side aisle.

There is a large mosaic of a cross in the apse, that was constructed by the iconoclast emperor, Constantine V. It is an interesting and unique piece of iconoclastic art, compared to the depictions of the Theotokos and Christ Child or Christ Pantokrator which typically adorned Roman churches.

The iconoclastic style would survive in the empire for over two centuries, characterized by geometric patterns and foliage. In a way, it may have been influenced by Middle Eastern schools of theology and art.

The church was built in the style of a late Roman basilica, consisting of a nave and two aisles. The aisles are supported by columns, many of which bears the unique monograms of the emperors who were instrumental in its construction – Justinian and Theodora. Beneath a couple of the columns, there are also marble slabs bearing the monogram of Constantine V.

Hagia Eirene is also home to a synthronon – rows of built benches that are arranged in a semicircle in the apse. It is here that the clergy would be seated during the Divine Liturgy. Quite common in Orthodox churches, the synthronon of Hagia Eirene is the only Byzantine example to survive until this present day.

An Imperial Tomb

One of the most tragic realities of classical history is that there are next to no surviving burials of Roman Emperors. The Crusaders and Ottomans would largely see to that. However, in the atrium of Hagia Eirene I noticed the presence of a porphyry sarcophagus. There is a cross on the lid and it is clearly the saprophagous of a deceased emperor. I can only speculate as to how it found its way to this location, as I know of no emperor that was entombed in Hagia Eirene.

The tomb is almost certainly that of a pre-1204 emperor, and originally rested in the Church of the Holy Apostles before being looted during the Fourth Crusade. It is next to impossible to ascertain if the tomb is that of Constantine himself or of one of his successors. At one point or another, the sarcophagus was moved from the church to Hagia Eirene before the Church of the Holy Apostles was demolished in 1461, in order to make way for the Fatih mosque. Other imperial sarcophagi survived as well, and can be found in the nearby Istanbul Archaeology Museum.

Armory, Military Museum, and Concert Hall

Unlike most other examples of Roman churches in Constantinople, Hagia Eirene was never converted to a mosque. Early after the Ottoman conquest, it became a type of office for the sultan’s Greek officials. However, soon afterwards, it would become enclosed in the complex of the Topkapi Sarayi (Topkapı Palace in Istanbul) and the area was taken over by Janissaries and the church would become their armory. It would remain so until the Janissary Corps were disbanded in 1826.

As early as 1726, Hagia Eirene was already in use as a home for trophies of arms captured by the Turks. Photographs from the late nineteenth century even depict the chain that once guarded the entrance to the Golden Horn. It is possible that the imperial sarcophagus was kept there as a military trophy.

Today, Hagia Eirene is silent, almost eerie. Only the cold stonework remains to tell the tale of this most fascinating church and the history that it has seen. The silence is so strong that one could hear a pin fall, were there anyone to drop it.

The church’s acoustics are so impressive that at times, the silence is occasionally interrupted by the classical music concerts that are held here. Thus, it remains with Hagia Eirene, a fascinating example of Byzantine architecture whose advantageous position next to the great Hagia Sophia has almost rendered it forgotten to history.