In Bucharest on Franceză Street, nestled between the bustling cafes, inviting restaurants, and crumbling, yet still inhabited homes of the old city, lies the ruins of the former Wallachian Voivodal Palace. While the complex has been closed for renovations throughout much of the decade, I had the opportunity to visit its arched gateways and subterranean chambers a few years ago while they were still accessible to the public. The ruins of the Voivodal Palace and Princely Court provide an exciting window into medieval Bucharest, prominently displaying the city’s important status in the Wallachian principality.

During the reign of Vlad Țepeș, it is known that one of the early capitals of Wallachia (Known in Romanian as: Valahia, Țeara Rumânească, and Цѣра Рȣмѫнѣскъ) was located at Tîrgoviște. However, the rising power of the Ottoman Empire forced the voivode to pay increasing attention to his southern border along the Danube, necessitating the inevitable rise of Bucharest as a major city within the Wallachian lands.

It is believed that the Wallachian rulers often held court here as early as the fourteenth century during the reign of Mircea the Old. However, it was under Vlad that the complex became a major fortress from where he could project power towards Giurgiu, which was then occupied by the Turks. There are records from as early as 1458 in which Vlad issued documents attesting to the fortress’s importance. In the said documents, he wrote to the people of Brașov, asking for their services in constructing the walls of the fortress.

The palace’s ruins could be entered through a bricked archway, possessing a small column near the entrance, a reminder of the Byzantine origins of the architectural style. Beneath, there are residences, chancelleries, and reception halls. The brick styles suggest that the building had been constructed, destroyed, and reconstructed at various moments of its history.

The chancery’s now cold and silent halls only holds echoes of the warmth and life that once held court here. It is almost certain that there are halls and tunnels go far deeper than I was able to visit, considering that it is possible to see even more medieval chambers beneath the nearby building of the Romanian National Bank. I do not know if it is possible to explore this area, as I have never tried.

The courtyard now holds the distinction of being an archaeological garden, full of broken stonework. It is important to note that Vlad Tepeș was not the first Wallachian ruler to inhabit the fortress, but rather his brother – Radu the Beautiful. During the endless dynastic wars plaguing the region, the Moldovans under Ștefan the Great besieged the fortress 1473 aiming to overthrow Radu and place Vlad back upon the Wallachian throne. Ștefan would go on to burn and raze the Bucharest fortress after his victory, but the palace complex would ultimately be repaired and extended.

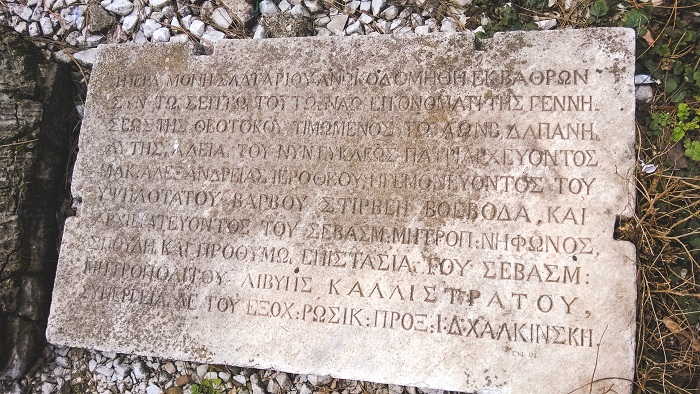

The palatial complex’s exterior is littered with stone crosses and inscriptions, written mostly in Slavonic, medieval Romanian (in the Cyrillic script), and Greek. These inscriptions may have once been located inside the palace’s halls, but have since moved outside as the complex fell into ruin, considering that the exterior courtyard once functioned as a garden.

Over the next century, Bucharest’s tîrg and strategic importance had expanded to the point that the Wallachian rulers made a permanent residence out of the palatial complex and the town became the capital of the principality. The nearby „Buna Vestire” church was constructed by Mircea the Shepherd in 1545 and is the oldest surviving church in the city. Similar to the palatial complex, the church was built in a combination of Byzantine and Moldovan styles. It is here that the rulers of Wallachia would be crowned over the following centuries, even if the palace itself fell into disuse and was eventually abandoned by the end of the eighteenth century.

Unfortunately, as previously mentioned – the palatial complex cannot be visited today. It is currently in a state of reconstruction and I cannot fathom of what its future state will be as a museum so I hope that this note will serve as a memorial for the Princely Court’s authentic shape and state in situ, lest it is lost to history.