I have a deep fascination and passion for cartography – historical cartography in particular. It is very enjoyable to pour over curiously drawn medieval maps – crude attempts to depict the shape of the world, and marvel at the symbols used to depict cartographic and natural phenomena. Roman cartography is poorly understood, as next to no examples survive from their once-flourishing works – and most of those are medieval copies of Roman originals. One such work – the Tabula Peutingeriana, provides the first known depiction of Constantinople in mapmaking.

On May 11, AD 330, Emperor Constantine dedicated his newly built city of Constantinople as the new capital of the Roman Empire; moving the seat of power from a decaying Rome to the shores of the Bosporus. Many senators and their families made the journey east, settling in the new capital. This new and vibrant city was decorated with palaces, forums, Greco-Roman temples, and Christian churches. Among the sights of Constantinople was a triumphal column dedicated to the emperor himself. The Column of Constantine stood over 165 feet tall, and was constructed of several cylindrical porphyry blocks, likely mined in Egypt.

Most impressively, the column was topped with a large statue of Constantine, in the appearance of Apollo and holding an orb. Legends state that the interior of the orb held a fragment from the True Cross. The column’s sanctuary also housed the Palladium, a small statue that the Romans’ Trojan ancestors had originally brought to Italy from the destruction at Troy. In an era before a church stood on the site of the future Hagia Sophia, the Column of Constantine was clearly designed as the principal monument of his new, religiously ambiguous city.

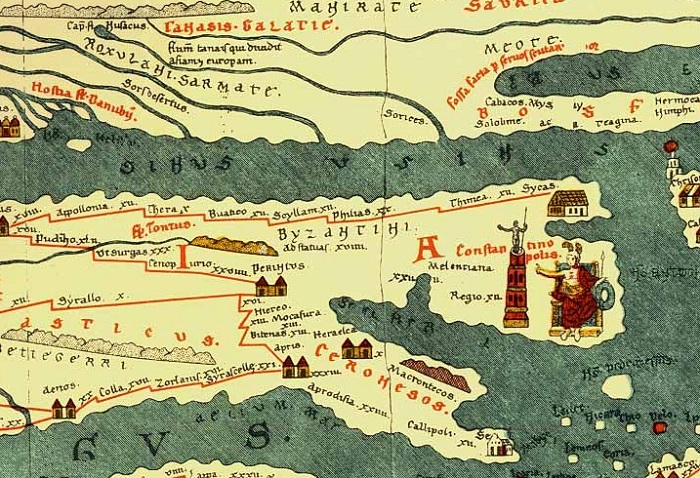

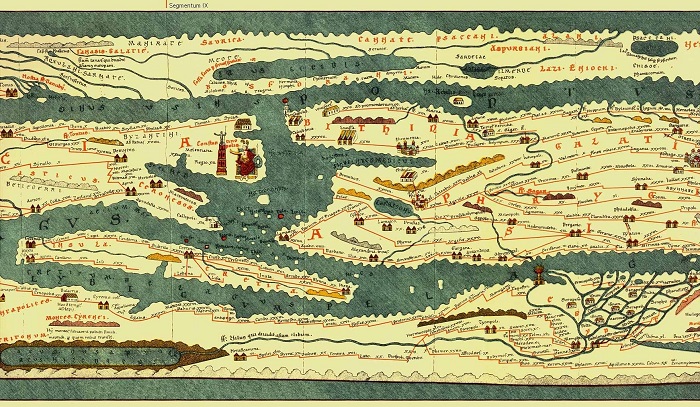

It is believed that the original map from which the Tabula Peutingeriana is based on was drawn in the 4th or 5th century due to its depictions of Constantinople. The map depicts most of the Roman Empire, including the city of Rome enthroned as a place to which all roads lead. Constantinople is also prominently depicted – with an emperor sitting upon a throne. Next to the throne is an important landmark – the Column of Constantine. The porphyry column topped with the statue of Constantine is apparent and the city is depicted as being at least the equal of Rome.

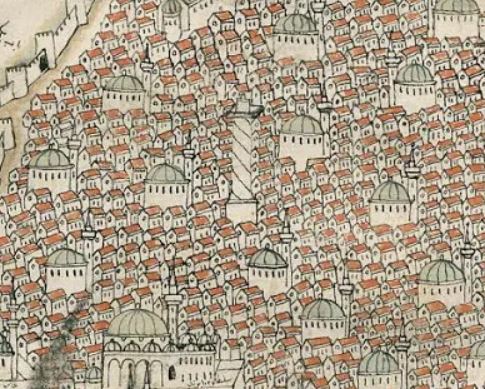

As the fortunes of the Roman Empire ebbed and flowed over the centuries, so too did the fate of Constantinople’s monuments. Palaces fell into disuse, the Hippodrome lost its function and became a ruin, and many churches and works of art were destroyed by the Franks and Latins during the Fourth Crusade. In 1422, the Florentine traveler and cartographer Cristoforo Buondelmonti created a map of Constantinople that depicts the column in a new state.

As the story goes, in 1106 a strong gale blew across the city that toppled the statue of Constantine, destroying it, along with three of the upper cylinder layers. A few decades later, Manuel I Komnenos, emperor of the Romans, replaced the fallen statue with a cross. Buondelmonti’s map depicts this iteration of the column in his map – a prominent landmark in the rather pitiful state of late Byzantine Constantinople.

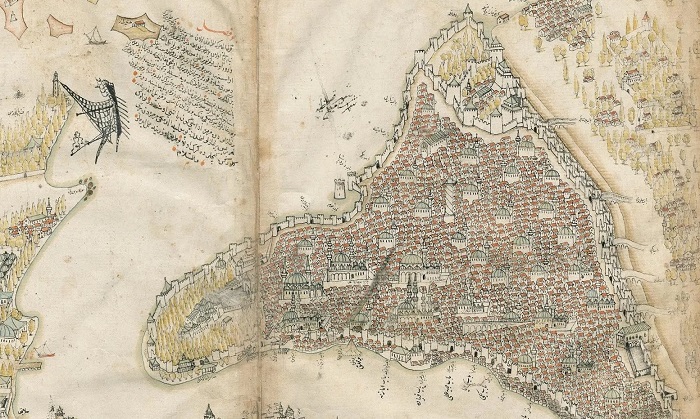

The famous Ottoman navigator Piri Reis was renowned for his cartographical works, including his famous map depicting the South Atlantic (and perhaps Antarctica). In his work, Kitab i-Bahriya (Book of the Sea) can be found a very accurate depiction of Constantinople dating to only a few decades after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks. On the map, published in 1521, the Column of Constantine is still prominent among the many spires and minarets of the city’s mosques. However, the cross is now missing from the column, having been taken down by the victors after the city’s fall in 1453.

Even today, the column is an important and noticeable landmark in Istanbul. In my own travel to the city, I was pleasantly surprised to find that it was located so close to my hotel. Familiar with the medieval and early modern cartographic depictions of Constantinople, I was easily able to use it as a reference point to discover the location of many of the other monuments, churches, palaces, and mosques that can still be seen and visited in Istanbul.

The column is today known as the Çemberlitaş, or “hooped stone” to the locals. Its former reddish-purple hue is no longer visible due to a fire that ravished the column in 1779, leaving it with blackened scorch marks and earning it the moniker “burnt column.” Sultan Abdulhamid repaired the damage to the column, and had its present masonry base added to it. More recent renovation work has replaced the iron hoops and have stabilized the structure, hopefully preserving it for the next few centuries. Until then, Constantine’s column still graces the Çemberlitaş with its presence, holding witness to the city’s history, and a landmark for cartographers both past and present.